Here are some excerpts from another Scalia article. Michelle Alexander (

Why Hillary Clinton Doesn't Deserve the Black Vote) should read this; she wouldn't be so quick to heap blame on Clinton for his policies. Maybe it'll also help some righties understand why liberals don't want another Scalia on the bench.

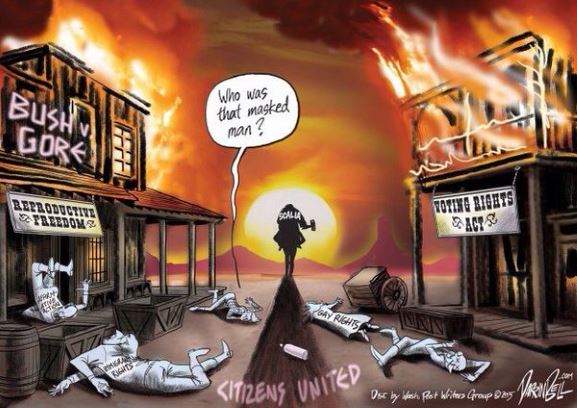

"In the days since Antonin Scalia’s death, he has been duly recognized as one of the most impactful justices in the Supreme Court’s history. A critical part of his troubling legacy has long been staring us in the face, although it finally started receiving

the public scrutiny it deserves in recent years. As draconian punishments became the norm over the last three decades, the Supreme Court largely rubber-stamped these practices. Justice Scalia played a key role in this process, as his hardline stances on criminal punishment significantly contributed to mass incarceration, numerous executions, and systemic racial discrimination. Scalia was an outspoken supporter of harsh punishments and wanted the court to take an even more hands-off attitude toward so-called “tough on crime” laws.

Not long after he made it onto the court in 1986, Scalia’s influence on these issues began to be felt. In

McCleskey v. Kemp, one of the first cases he heard, anti-death penalty advocates brought compelling evidence of pervasive racial discrimination in Georgia’s administration of capital punishment. A sophisticated statistical study demonstrated that sentencing was tied to the race of the victim and offender. All other factors being equal, blacks who killed whites were the likeliest to receive a death sentence. Justice Scalia was unfazed. During oral arguments, he derisively

asked: “What if you do a statistical study that shows beyond question that people who are naturally

shifty-eyed are to a disproportionate extent convicted in criminal cases, does that make the criminal process unlawful?”

Had Scalia had his way, far more people would have been executed during his tenure and the court would have adopted an even more accommodating approach to mass incarceration. In his view, merciless punishments were just deserts for “

evildoers.” He

scoffed when fellow justices advanced a more nuanced view of criminal behavior or occasionally suggested that draconian punishments were dehumanizing. He was certain that the court already

cared too much about people who faced the death penalty or endless prison sentences. Justices who disagreed with him were

judicial activists who refused to defer to elected branches of government.

John Charles Boger, who represented the black death-row prisoner in

McCleskey, responded by pointing to the obvious: “This is not some sort of statistical fluke or aberration. We have a century-old pattern in the state of Georgia of animosity [toward black-Americans].” Scalia and four other justices nonetheless chose to analyze discrimination out of its social context, including in cases from Southern states with a lengthy history of slavery, segregation, and lynchings.

Scalia was in the majority as the court held that statistical proof of systemic discrimination in the death penalty is irrelevant. A defendant must instead prove intentional discrimination in his own case, an almost impossible standard without considering systemic patterns. Many experts

consider McCleskey among the worst Supreme Court decisions of all-time. It largely

closed the door to statistical evidence as a means of challenging systemic discrimination in criminal punishment.

Scalia would also play a significant role as the Supreme Court licensed ruthless sentences leading America to

world record incarceration levels. He wrote the operative part of the influential

Harmelin decision, a 1991

plurality opinion holding that theEighth Amendment ban on “cruel and unusual punishments” does

not require that a prison sentence be “proportional” to the crime. The court thus upheld a life-sentence for cocaine possession.

Scalia again was in the majority in

Lockyer v. Andrade, a 2003 case upholding a 50-year-to-life sentence under California’s three-strikes-law for a man who shoplifted videotapes worth $153 because he had prior convictions for petty theft, burglary, and transporting marijuana. Erwin Chemerinsky, who zealously represented the prisoner,

was in tears as the media asked him about his reaction to the court’s inhumane decision.

McCleskey,

Harmelin, and

Lockyer were all 5–4 decisions that could have been decided otherwise if Scalia had thought differently. Naturally, he was not a swing vote but a sure one for harsh justice. While the justices might not have been able to stop mass incarceration singlehandedly, they definitely could have limited it. Indeed, the court’s belated decision in

Brown v. Plata, has

contributed to reducing California’s incarceration rate. In this 2011 case, the court

ordered California to reduce its dramatically overcrowded prison population because “depriv[ing] prisoners of basic sustenance, including adequate medical care, is incompatible with the concept of human dignity.” In a vehement

dissent, Scalia charged that this was “a judicial travesty” and that the majority was “wildly” overstepping its authority.

Similarly, he fiercely dissented in other rare cases where the court decided to check ruthless punishments. If it had been up to Scalia, it would still be constitutional to execute

mentally retarded people or

teenagers, not to mention sentence teenagers to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for

homicide or

any other crime.

(Continued)

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_...de_america_s_incarceration_problem_worse.html

You always show just who you are in your posts. There are fewer whites than blacks in prison for the same crimes, and whites get lesser sentences. That's just the facts. Even the right-leaning WSJ admits it.

You always show just who you are in your posts. There are fewer whites than blacks in prison for the same crimes, and whites get lesser sentences. That's just the facts. Even the right-leaning WSJ admits it.