signalmankenneth

Verified User

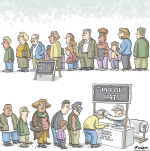

Measles have surged to a record high, with more cases reported this year than any year since the disease was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000.

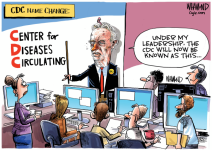

This disappointing record comes amid falling childhood vaccination rates: Coverage against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, polio and pertussis is declining in more than 30 states, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Some people may believe that if they’re personally vaccinated, they have nothing to worry about. But is individual protection enough when contagious illnesses start multiplying? How will falling vaccination rates result in the return of previously eliminated diseases? Will only children be affected, or could adults see an impact as well? Who would be at highest risk if there is lower population-wide immunity? And what can be done to prevent this possibility?

To get some answers, I spoke with CNN wellness expert Dr. Leana Wen. Wen is an emergency physician and clinical associate professor at George Washington University. She previously was Baltimore’s health commissioner.

Dr. Leana Wen: Yes. There are numerous examples around the world. Countries that were once polio-free have had polio outbreaks due to interruptions in childhood immunization programs caused by war and conflict. Measles outbreaks have occurred in countries where measles had been eliminated, due to falling vaccine coverage.

This, in fact, is what we are seeing now in the US. In Texas, 753 measles cases have been confirmed since January. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, 98 of these patients have been hospitalized, and two people, both children, have died. This outbreak is believed to have originated in communities with low vaccination rates.

What could happen if childhood vaccination rates declined further? A recent study published in JAMA predicted that a 10% decline in measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine coverage could result in more than 11 million measles infections over 25 years. A 50% decline in routine childhood vaccinations could result in 51 million measles cases, 9.9 million rubella cases and 4.3 million polio cases.

The projections also included the number of people affected by severe consequences of these diseases: As many as 10.3 million people in the US could be hospitalized, 159,200 could die, 5,400 could experience paralysis from polio, and 51,200 could have neurological consequences from measles.

Wen: They should still worry for three main reasons.

First, while many vaccinations provide excellent protection against disease, there is still a chance of breakthrough infections — meaning that the vaccine doesn’t provide 100% protection. Two doses of the MMR vaccine are 97% protective against measles infection, which is an outstanding level of protection. But it’s not 100%, so if someone is exposed to measles, there is still a chance they could become infected. However, vaccination substantially reduces the likelihood of infection and also of having severe disease if they were to become infected. The more disease there is in the community, the higher the likelihood of exposure and infection.

Second, there may be some waning of vaccine effectiveness over time. For instance, according to the CDC, immunity to pertussis — also known as whooping cough — starts to wane after a few years following vaccination. Older adults who received childhood vaccinations many years ago may become susceptible if previously controlled childhood diseases make a comeback.

Third, there are people who are unable to receive the benefit of vaccination directly themselves. Some people are unable to receive certain vaccines because of specific medical conditions. For instance, someone who has a weakened immune system may not be able to get the MMR vaccine because it contains a live, weakened form of the virus.

Also, some people may have medical conditions that render vaccines less effective at protecting them. These individuals depend on the rest of society — those who can receive the vaccine — to do so and try to prevent these diseases from spreading.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/diseases-could-return-vaccination-rates-213619393.html

This disappointing record comes amid falling childhood vaccination rates: Coverage against measles, mumps, rubella, chickenpox, polio and pertussis is declining in more than 30 states, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Some people may believe that if they’re personally vaccinated, they have nothing to worry about. But is individual protection enough when contagious illnesses start multiplying? How will falling vaccination rates result in the return of previously eliminated diseases? Will only children be affected, or could adults see an impact as well? Who would be at highest risk if there is lower population-wide immunity? And what can be done to prevent this possibility?

To get some answers, I spoke with CNN wellness expert Dr. Leana Wen. Wen is an emergency physician and clinical associate professor at George Washington University. She previously was Baltimore’s health commissioner.

Dr. Leana Wen: Yes. There are numerous examples around the world. Countries that were once polio-free have had polio outbreaks due to interruptions in childhood immunization programs caused by war and conflict. Measles outbreaks have occurred in countries where measles had been eliminated, due to falling vaccine coverage.

This, in fact, is what we are seeing now in the US. In Texas, 753 measles cases have been confirmed since January. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, 98 of these patients have been hospitalized, and two people, both children, have died. This outbreak is believed to have originated in communities with low vaccination rates.

What could happen if childhood vaccination rates declined further? A recent study published in JAMA predicted that a 10% decline in measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine coverage could result in more than 11 million measles infections over 25 years. A 50% decline in routine childhood vaccinations could result in 51 million measles cases, 9.9 million rubella cases and 4.3 million polio cases.

The projections also included the number of people affected by severe consequences of these diseases: As many as 10.3 million people in the US could be hospitalized, 159,200 could die, 5,400 could experience paralysis from polio, and 51,200 could have neurological consequences from measles.

Wen: They should still worry for three main reasons.

First, while many vaccinations provide excellent protection against disease, there is still a chance of breakthrough infections — meaning that the vaccine doesn’t provide 100% protection. Two doses of the MMR vaccine are 97% protective against measles infection, which is an outstanding level of protection. But it’s not 100%, so if someone is exposed to measles, there is still a chance they could become infected. However, vaccination substantially reduces the likelihood of infection and also of having severe disease if they were to become infected. The more disease there is in the community, the higher the likelihood of exposure and infection.

Second, there may be some waning of vaccine effectiveness over time. For instance, according to the CDC, immunity to pertussis — also known as whooping cough — starts to wane after a few years following vaccination. Older adults who received childhood vaccinations many years ago may become susceptible if previously controlled childhood diseases make a comeback.

Third, there are people who are unable to receive the benefit of vaccination directly themselves. Some people are unable to receive certain vaccines because of specific medical conditions. For instance, someone who has a weakened immune system may not be able to get the MMR vaccine because it contains a live, weakened form of the virus.

Also, some people may have medical conditions that render vaccines less effective at protecting them. These individuals depend on the rest of society — those who can receive the vaccine — to do so and try to prevent these diseases from spreading.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/diseases-could-return-vaccination-rates-213619393.html