In early 1973, as Joe Biden was settling into his new job in Washington, DC, Ralph Nader published a deconstruction of what made the freshman DEMOCRAT senator’s state of Delaware, the most anodyne of states, so exceptional.

The answer, The Company State explained, had to do with the unique relationship between government and commerce: Delaware was less a democracy than a fiefdom, contorting its laws to meet the demands of its corporate lords.

Preeminent among them was the chemical giant DuPont.

Nader took readers to Rodney Square, in the heart of Wilmington.

There was the ritzy Hotel du Pont, housed in a building owned by DuPont, next to a theater built by DuPont, connected to a bank controlled by the du Pont family, surrounded by law offices and brokerages—all affiliated in some way with what was known simply as “The Company.”

The du Ponts owned the state’s two largest newspapers and employed a tenth of the state legislature.

The governor was a former executive.

The state’s member of Congress for most of the 1970s was Pierre Samuel du Pont IV.

“General Motors could buy Delaware,” Nader quipped, “if DuPont were willing to sell it.”

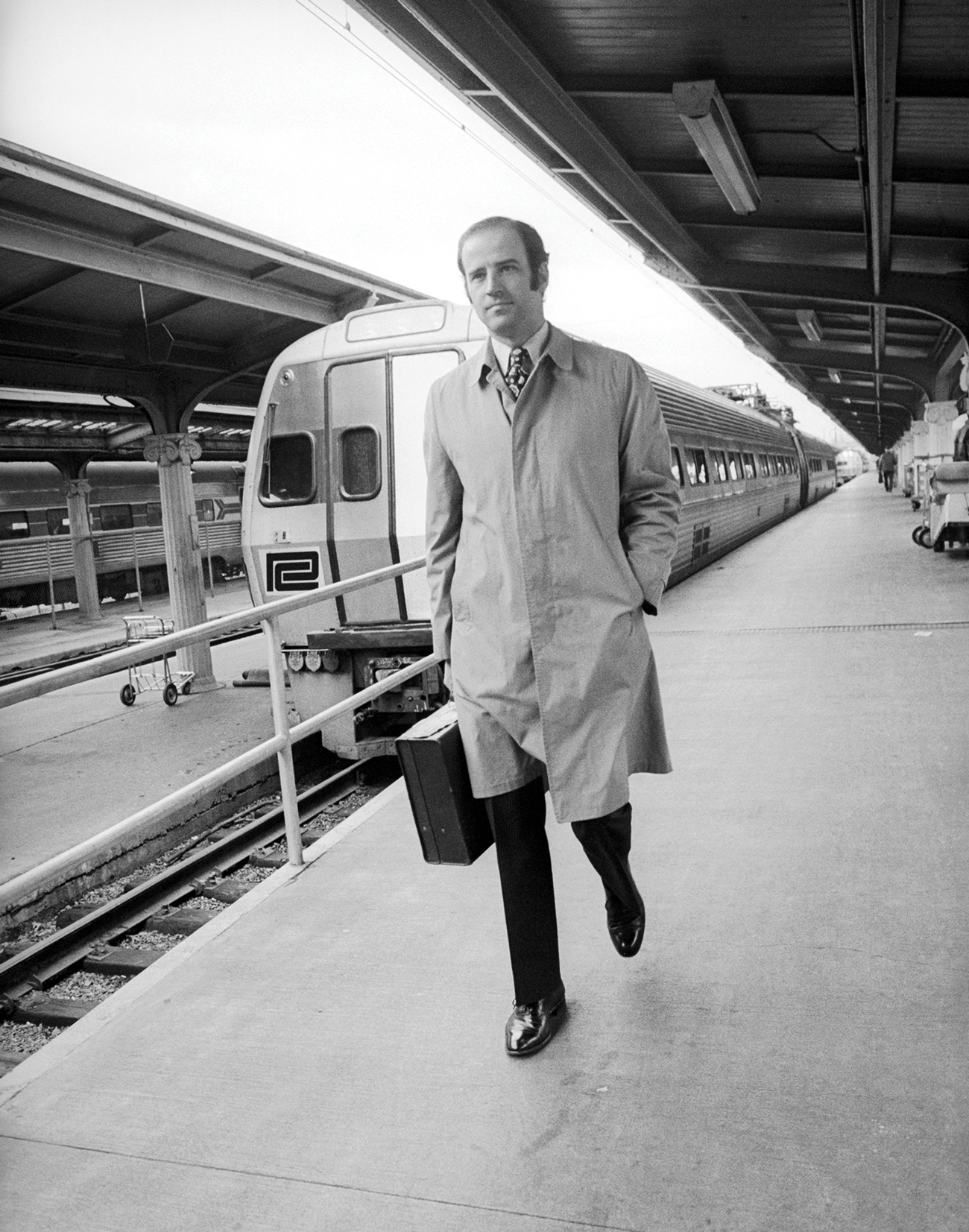

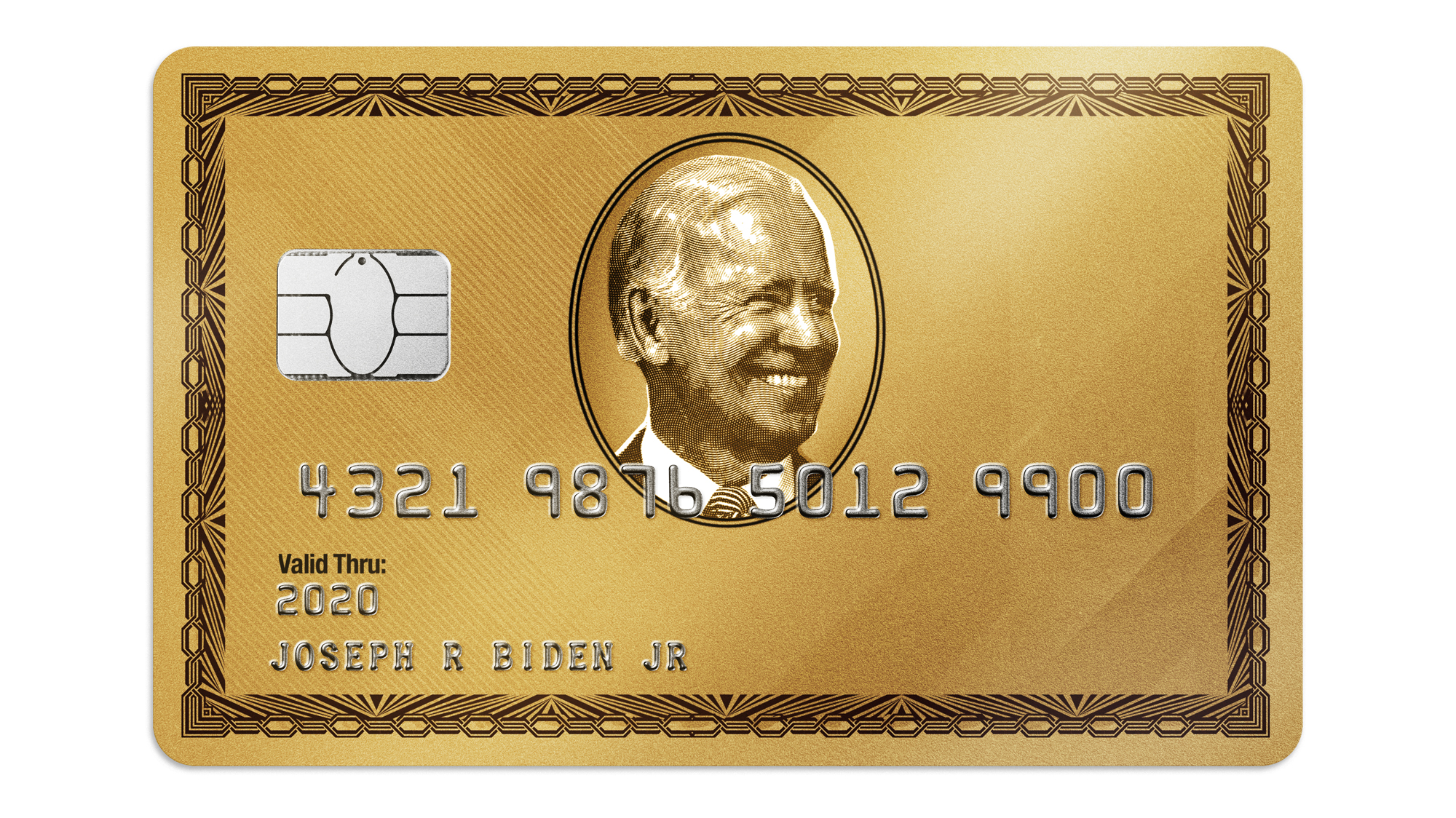

Over the next two decades, as Joe Biden rose through the ranks of the DEMOCRAT Party, the state’s center of gravity began to shift from the world of chemicals to the big business of other people’s business—banking, accounting, law, and telemarketing.

But if the industry had changed, the ethos remained: Delaware was the Company State. It owed its prosperity to its willingness to give corporations what they wanted.

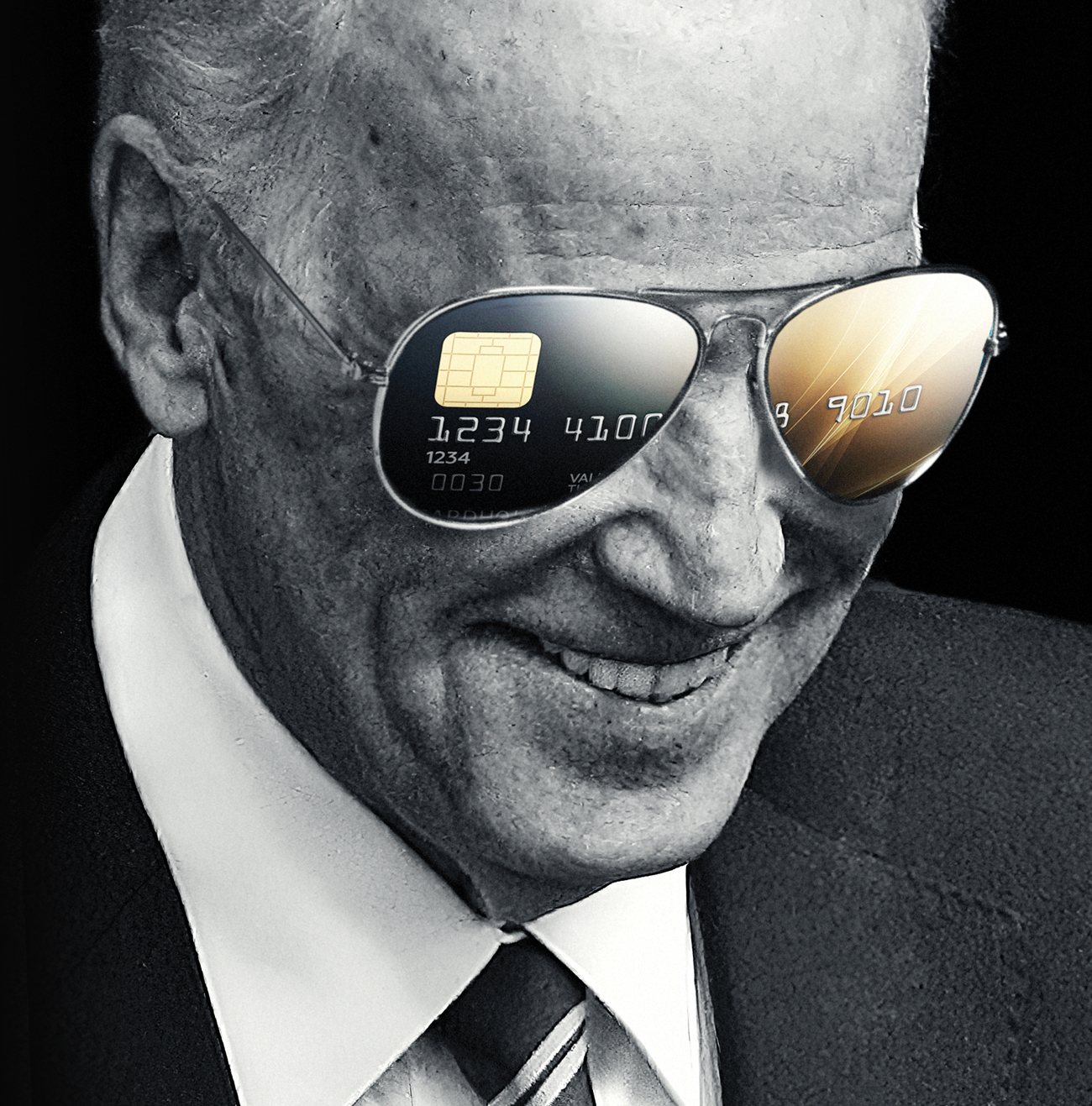

Though he’s now a millionaire, Biden has long positioned himself as the champion of the middle class, a scrappy kid from Scranton who’s fought the good fight for decades.

His adopted home state is part of that identity too—an unglamorous enclave of scrapple and toll roads, the Acela Corridor’s own Flyover Country.

But as he pursues his third and likely final quest for the presidency, his record haunts him, because the interests of Delaware are often at extreme odds with everyone else’s.

Biden did not create this system, but he used his influence to strengthen and protect it.

He cast key votes that deregulated the banking industry, made it harder for individuals to escape their credit card debts and student loans, and protected his state’s status as a corporate bankruptcy hub.

Biden’s career in the Senate placed him on the wrong side of some of the biggest financial fights of his generation and brought him into conflict with some of the same rivals he faces today.

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2019/11/biden-bankruptcy-president/